Autism Acceptance Month – a shift from the prior messaging of April as Autism Awareness Month – reflects the importance of making space for all kinds of minds, including those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Temple Grandin, PhD, who was diagnosed in childhood with ASD, recently shared with us that even 12 years after her highly viewed TED talk, The World Needs All Kinds of Minds, this idea still holds true. She opened a recent phone interview with us, “Yes, absolutely, the world needs all kinds of minds, especially those with ASD.” Dr. Grandin extends this work in her new book, Visual Thinking.

The reality is that many minds are great, and not one of them thinks alike. More than ever we need differently thinking minds to generate answers to persisting problems: climate change, health care inequity, infectious disease, etc. And, Dr. Grandin stressed to us, “Collaboration is key.”

In general, people with ASD tend to understand the world in a bottom-up manner. Imagine you are working on a puzzle, and all the pieces were blank – you could only see the individual shapes and how they fit together. However, once you finished the entire puzzle, the picture appeared. This is an illustration of bottom-up thinking: where details precede the “big picture.” This thinking is typically more characteristic of individuals with ASD and can lead to making outside-the-box connections and inventing novel solutions to problems.

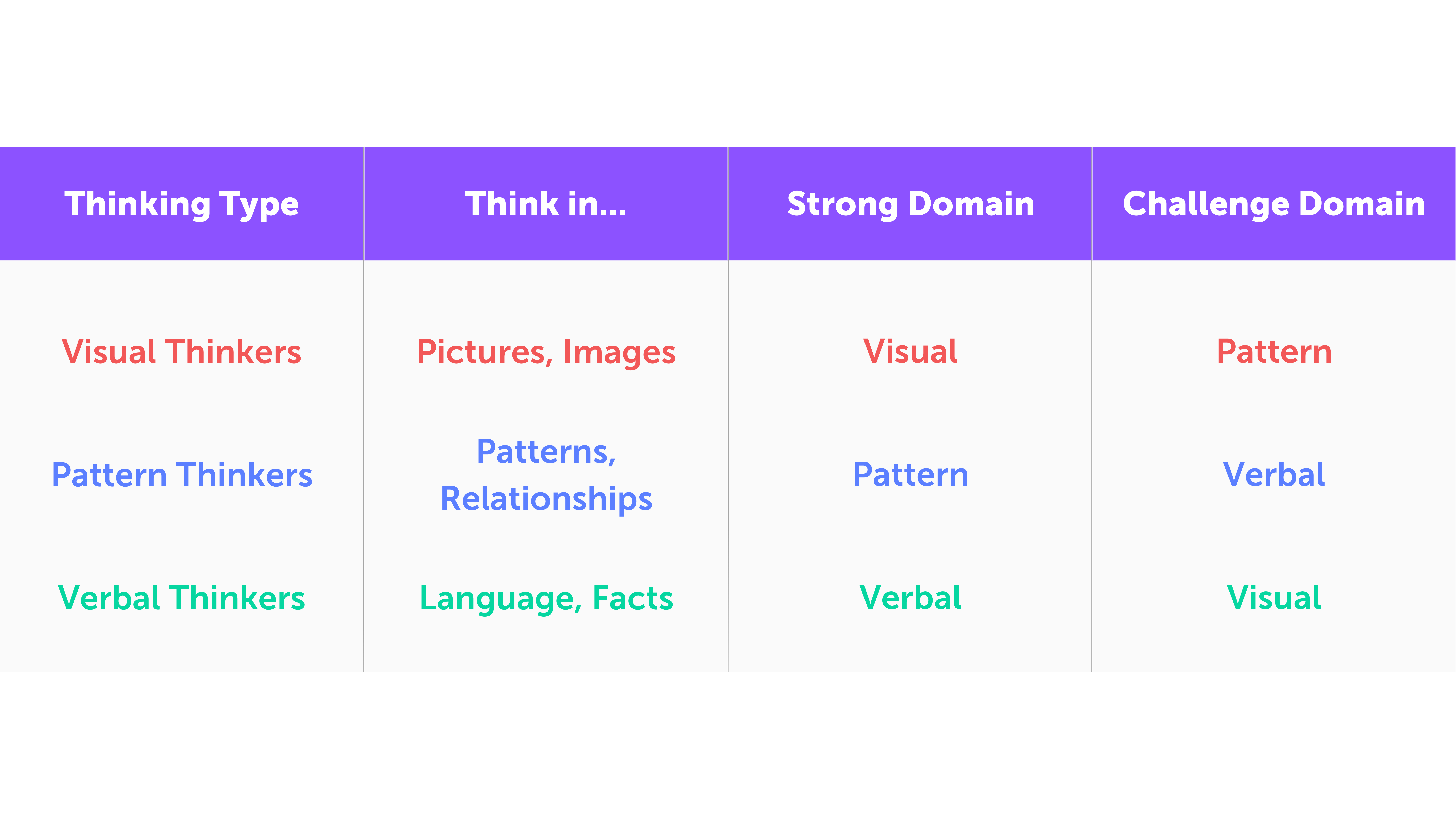

There are three defined types of specialist thinking related to ASD: Visual Thinkers, Pattern Thinkers, and Verbal Thinkers – all with their strengths and challenges. Our world is built for the neurotypical. Consequently, these specialized thinkers are often regarded in terms of their challenges as opposed to their unique strengths. Further, Visual, Pattern, and Verbal Thinkers naturally complement one another – where one is challenged, the other is strong (Figure 1 below). Making space for different types of minds means optimizing for their counterpart gifts and fostering neurodivergent acceptance.

Visual Thinkers

Visual Thinkers

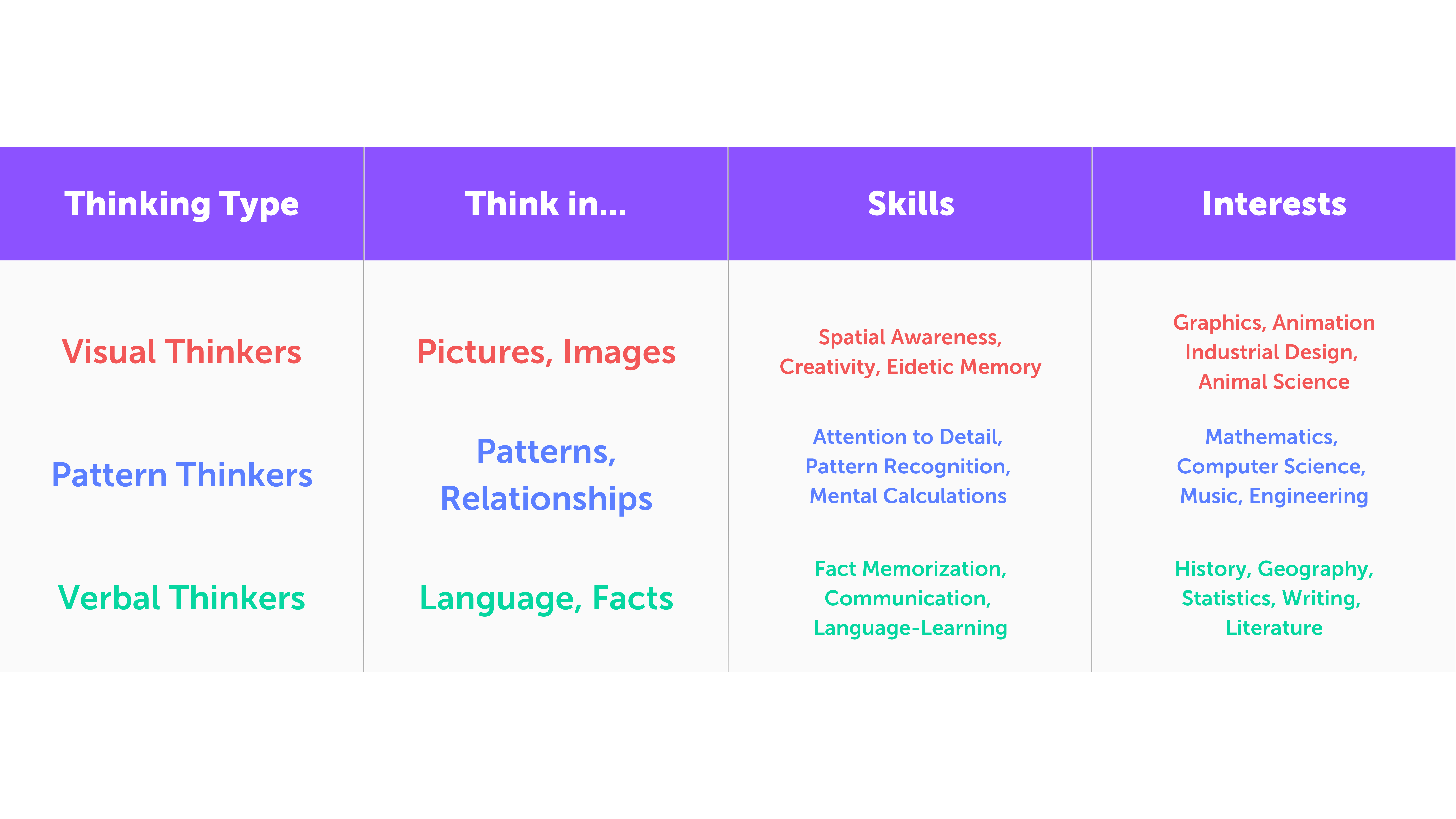

The most well-defined form of specialized thinking in people with autism is Visual Thinking. Visual Thinkers are typically creative and hypervisual, processing information through photorealistic images. Temple Grandin, a noted Visual Thinker, describes her mind as an “Internet search engine,” where having a thought is like querying Google Images, her mind navigating through a vast database to locate a target idea represented by an image. This capacity to think in pictures makes it possible to remember large amounts of visual information, invent complex systems, and run advanced simulations in the mind’s eye.

There is a neurological basis for the strong visual skills in Visual Thinkers. In a High-Definition Fiber Tracking (HDFT) map of Grandin’s brain, researchers found that the volume of neuronal projections from the visual cortex to the motor cortex was 10 times larger than the control. This enhanced connection accounts for her comparatively heightened visuospatial processing and memory.

The Visual Thinker has incredible spatial awareness, creativity, and visual memory. These skills naturally translate into success in visual arts and industrial design fields. Because Visual Thinkers are challenged with abstract thinking and math, they are complemented by Pattern Thinkers.

Pattern Thinkers

Pattern Thinkers

Patternicity is the ability to perceive meaningful patterns in apparently meaningless data. Pattern Thinkers are those whose minds engage with the world through patternicity. This type of mind excels in areas that are grounded in patterns, like music and math. Pattern Thinkers, therefore, tend to possess exceptionally strong attention to detail, mathematical skills, and pattern recognition. The strengths of this thinking type make Pattern Thinkers uniquely suited to occupations that involve handling big data, statistics, and formulas. Robotics, engineering, computer sciences, statistics, and music are fields where Pattern Thinkers can thrive.

While Pattern Thinkers are gifted in associative and pattern-based tasks, adapting to environmental inconsistencies can be an obstacle. A case study on the needs of young students with ASD demonstrated that Pattern Thinkers benefit from reconstructing intangible experiences, such as good and bad behavior, into tangible ones, such as a behavior management point system. For example, a young Pattern Thinker named Devin was awarded points throughout the day for positive behavior which he could later redeem for incentives. This individualized behavior system reduced Devin’s outbursts during class and increased the quantity and quality of his independent work.

The Pattern Thinker has uncanny abilities like playing music by ear or performing savant-like mental calculations, recognizing relationships that no one else can. Pattern Thinkers are generally challenged with reading and writing composition, where patterns are not as accessible. As a result, Pattern Thinkers are complemented by Verbal Thinkers.

Verbal Thinkers

Verbal Thinkers

There are estimated to be between 25% and 30% of the total ASD population that are minimally verbal or nonverbal. This may explain why there exists such a scarcity of information on the Verbal Thinking type in autism.

Verbal Thinkers are people with ASD who think only in word details. As a result, the Verbal thinking type has a large capacity for retaining verbal facts, learning languages, and communicating complex information. They have an affinity for facts and statistics, often compiling lists and memorizing long sequences of written data (e.g., instructional manuals, public transportation schedules, etc.). They are particularly skillful in logical consistency because, in the mind of the Verbal Thinker, cognition is mediated by the consistent structure of language. Verbal Thinkers often develop keen interests in areas like history, geography, statistics, and linguistics. Their unique interests and strengths can be leveraged to succeed in everything from writing to trivia competitions.

However, due to their reliance on words for conceptualization, Verbal Thinkers have difficulty with imagery and visual thinking. As Grandin maintains, “If I have no picture, I have no thought,” likewise do Verbal Thinkers lack the ability to process non-verbal information.

Accordingly, this obstacle of the Verbal Thinker can be complemented by the visual capabilities of the Visual Thinker.

This April for Autism Acceptance Month, we want to emphasize, counter to the popular phrase, great minds don’t think alike. Because of the long-held understanding of what “normal” thinking looks like, our world tends to view people with ASD in terms of their challenges. Reframing our idea of a “great mind” allows us to make space for all types of minds, helping them to flourish by recognizing their obstacles and optimizing for their strengths. We must bring all minds to the table, including those with ASD, to solve the world’s longest-standing problems. Great minds don’t think alike. Great minds think differently. Inclusion, acceptance, and collaboration with these minds are critical as truly, the world needs all kinds of minds.

Note: This content was originally published on Mind Matters from Menninger, our blog on PsychologyToday.com.